I spoke to Rob Thomsett and synth player Steve Durie about their experience making music together in the 1970s and how Yaraandoo came about.

Rob Thomsett: I was born in Brisbane and like I guess a lot of kids in the 50’s was forced to learn how to play the piano and gave it up very quickly. Then I joined the naval college in Jervis bay of all things, 1966 it was, I heard on a cheap transistor radio from Sydney the Rolling Stones playing ‘Not Fade Away’ and literally my life changed that day. So, I’ve always had a special spot for the Stones because they ended with me being thrown out of the navy cause we formed a little band playing Rolling Stones stuff in the naval college and of course officers never did that. We used to hoon up the Sydney and get Rolling Stone looks, you know shirts and stuff, so i was thrown out and moved to Canberra.

Rob Thomsett: Dylan was strong and all those guys and I ended up in a band with Fred Aubrey. He was an amazing player, and a guy called Kevin Abbey and a guy called Guy Holden, and we joined a jug band. Played a place called ‘Folk Blues and Beyond’ which was held in a church hall in Lyneham, but it was packed every Sunday night, it was packed, it was wonderful and there was no stage you just got up. So, that was the start of it and i was playing bass then, then I started to play guitar, started moving to guitar early 70’s and by that stage I had joined a band called Astral Plane and that was sort of in my opinion the beginning of the peak of the Canberra era in terms of the popular music. You know we were listening to guys like Jethro Tull and I learnt to play flute as well as guitar. So Astral Plane’s first incarnation did a lot of Tull stuff and of course you go back and that was sort of wonderful music the first few Jethro Tull albums were mind-blowing to me.

Jordie Kilby: Astral Plane are still really well remembered around Canberra these days as one of the best bands of their time. so, when the Hoadley’s battle of the bands came up they naturally entered.

Rob Thomsett: We went in and were beaten by Salty Dog which was a band Gunther Gorman had and they were a great band they did a lot of British blues rock stuff, and that was very important because we sort of had just been doing covers and I said, “You know screw that we’ll start writing our own stuff”, and the first thing we wrote, and I wrote fair bit of it, and Brian Fogwell who’s the other guitarist wrote a bit, it was a rock opera and it was incredibly pretentious, it was called Child Of The City and sort of had T.S Elliot quotes all over it and everything. We played it at Australlian National University and it was probably the first time in my life I understood what music was all about. Cause when we finished playing, we played for like an hour, we were over the top then, and we stopped playing and there was no sound, and I was just sort of oh well that was stuffed, then there was this incredible applause a good minute after we stopped playing and it was one of those really special moments. I always remember it. Just this stunned silence cause no one was doing that sort of stuff in Canberra in those days, playing totally original music and certainly not for a whole hour. It was a pretty seminal moment for me.

Jordie Kilby: Running off the buzz from that gig they went looking for other places they might be able to perform the piece.

Rob Thomsett: In those days it was really hard to find venues in Canberra, it was a lot smaller than it is now, and so a lot of times you just had to do it yourself. So, after we played at the ANU we hired The Playhouse. We all had day gigs so we all had a bit of money and we performed it again. And at that stage it was really clear to me, that’s what I wanted to do, which was just to dedicate to writing innovative stuff.

Jordie Kilby: There was a little spanner in the works though because not long after that Astral Plane broke up. But this turned out to be a blessing.

Rob Thomsett: John Hovell, who was the drummer, and myself joined two other guys Danny Goonan and John Socha who were in a really big band. I’m trying to remember their name but they did a lot of Cream stuff and things like that. We formed a band called Oak which stayed together for three years. In retrospect that was amazing stuff, we wrote all our own material and we put on three concerts once a year. We hired the Childers Street hall and they became really quite popular. I’ve got the posters, we silk screened our own posters. In fact, my wife Camille gave me one the concert posters for Christmas.

Rob Thomsett: Oak were real prog, really heavy two guitar lineup. I was playing flute by then and clarinet and harmonica as well. Again, a lot of it in retrospect was pretty self indulgent, but sort of around that era, that whole rock scene was exploding. There was Tully and Nutwood Rug Band and Jeff St John and The Id, and I think it was this wonderful blooming of people saying we can create any form of music we like and play it loud. With Oak we actually wrote three concerts and I’ve got tapes of all of them actually, and I put out two of the songs on one of my early cd’s when i got back to music in the early 2000’s. They’re pretty badly recorded. We used to play at a church in Lyneham and the oak tree was in front of it. That’s why we called ourselves Oak. At that stage my guitar playing was really becoming mature and the band was becoming great.

Jordie Kilby: In January of 1972, John Hovell approached keyboard player Steve Durie and asked him to join Oak.

Steve Durie: I knew of Oak because it formed out of probably some of the best-known original bands in Canberra, which was Astral Plane and Canyon, two bands coming together and forming ‘Oak’. I was well aware of them. I was impressed that they came and spoke to me and I had a session with him and met Rob that day and then spent 2 years working with him.

Jordie Kilby: During this period all the guys were expanding their musical horizons. There were some amazing Jazz fusion records coming out and they had a big impact on the style of the music that Oak began to play.

Steve Durie: Just in the tail end of the 60’s and the beginning of the 70’s you had this fusion of jazz and rock influences creating a whole bunch of different styles going. We were absorbing a lot of that stuff. Miles Davis and all of those bands that came out of Miles Davis, John McLaughlin stuff, Keith Jarrett, Herbie Hancock, Weather Report. I guess we were synthesizing our own thing, our own impression, what we could do with that from our limited technical capabilities. And the particular combination of people that we were and creating what was then a very original sound in Canberra, which was definitely in the rock vain but had very strong jazz influence in it.

Rob Thomsett: After the Child Of The City experience with Astral plane I really liked writing. Around about that same time I started crossing over into jazz. Bitches Brew was just unbelievable and really changed my attitude to music. Then all the spin-off bands from that wonderful era with Miles. So some of my ultimate favourite records still are out of that era: the first Weather Report album, the first Headhunters album. When we were in Oak I remember we spent an afternoon listening to the first Mahavishnu Orchestra, the Inner Mounting Flame album, and I can still remember that afternoon we just sat there. My wish is that everyone sits in a room once and listens to music and just, you know, just has their mind blown you know. That album was really important to me.

Jordie Kilby: Jazz and fusion weren’t the only influences running through the band. Steve Durie was soaking up the others whilst studying at the Canberra School of Music.

Steve Durie: I’d been playing the piano only a couple of years, other than a bit of tinkling as teenager, but I’d made a decision in 1970 that I’d actually go learn to play the piano. So, 70 and 71 I was studying the piano with a piano teacher and it was primarily classical stuff and in 71 I actually got into the school of music there and started studying composition with Larry Sitsky. So, I was coming from a recent but strong classical influence and then via Larry Sitsky getting exposed to contemporary music and Avant Garde musical influences. That was when I had the opportunity to join Oak.

Jordie Kilby: Most of the band had day jobs in the public service which enabled them to equip themselves with cutting edge technology and instruments.

Steve Durie: We had probably the first Mini-Moog synthesizer in Canberra and so that was very rare for a band to have a synthesizer in Canberra at the time. Larry Sitsky encouraged me at the time to take an interest in electronic music. Dawn Banks was out from the UK at that time doing a fellowship at the school of music at ANU and they set up an electronic music studio and I was one of several students at the school who was very involved with Dawn and the electronic music stuff there. I was doing all sorts of experimental work on a whole range of synthesizers that they had put together in that studio and as soon as Rob got on to that he said, oh gee, I’m gonna go and get you a synthesizer. He went and got a Mini-Moog himself and I came into band rehearsal one night and there’s this synth sitting there, so that became a primary instrument for me and obviously shaped a lot of the work I did in the band.

Jordie Kilby: With Oak jamming regularly and their ability to express themselves growing all the time Rob began to cast around for a story that the band could breathe some musical life into.

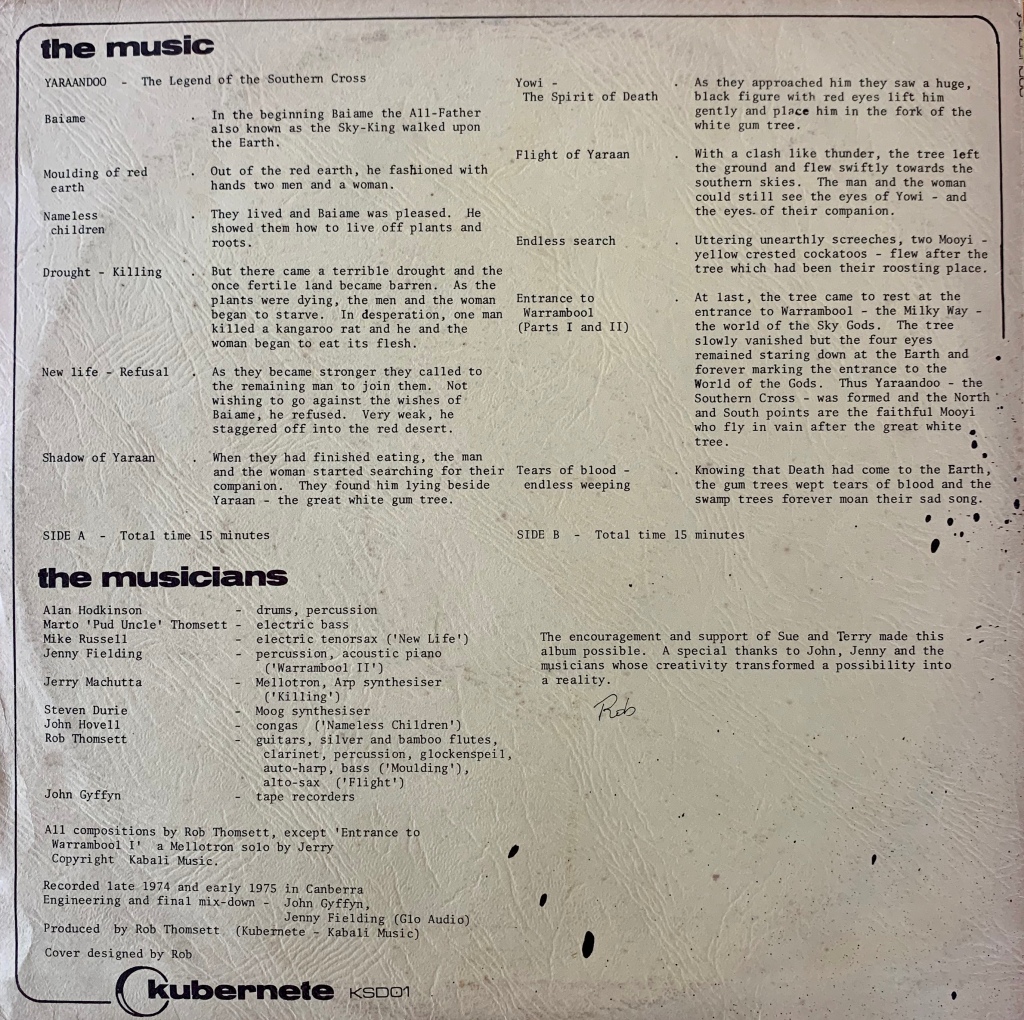

Rob Thomsett: I became really interested in what was happening to Australian Aborigines because, you know, I was raised in a traditional racist Queensland family. I went to the National Library and found a book on aboriginal myths and read the Yaraandoo myth and for those folks who don’t know it it’s just beautiful. God creates the earth, its two men and women, there’s a famine, which is a great story for Australia, and they’re all dying and gods ban them from killing. But they kill a kangaroo rat and offer it to the third guy who goes off and refuses it like he’s true to the faith and he dies and then this gum tree takes off with his spirit in it, with the dead guy, and carries the dead aborigine up to the milky way and creates the southern cross. Just breathtakingly beautiful story. Of course you can see the similarities from that story and most other creation stories and that got me really interested in a whole bunch of standard creation stories and that just inspired the hell out of me and I started writing.

Steve Durie: The introduction Rob gave to me was the story of the legend of Yaraandoo and the birth of the southern cross. He was really excited about the legend and at that point he was only imaging the music or I think he had a few different sketches of things he would like to do with it. But he was imagining putting together this suite of music centred around the aboriginal legend of Yaraandoo. He was very excited. I can remember him dancing around the room imitating the various characters of the legend; the cockatoos, the aboriginals, and the rest of it. It was one of those Rob Thomsett performances that’s really persuasive and really captures you into the spirit of what you’re doing.

Jordie Kilby: As the Yaraandoo project was maturing into 1974, Oak were beginning to split up but members like Steve Durie and John Hovell continued to work on the Yaraandoo with Rob Thomsett. They were joined by other local musicians like drummer Alan Hodkinson and bass player Mato Thomsett. The scope of the project quickly captured the imaginations of all the players involved.

Steve Durie: What we were doing with Oak was we were doing concert music. A lot of it was very danceable, but it was concert music for people to listen to. There were various themes presented but probably most of the Oak shows were only loosely connected in terms of the story line. It was generally more instrumental music that was abstract and yet here he was proposing that we take those skills and ideas and capabilities that we had from a musical point of view and apply them to tell a story. That was pretty exciting in itself.

Jordie Kilby: The rehearsals and recordings for Yaraandoo took place towards the end of 1974 and into the beginning of 1975.

Steve Durie: I had moved from Canberra to Sydney by the time that we got well into Yaraandoo. I was doing some work up there and I came back to Canberra for several sessions to participate. So, Rob was sending me material that I was working with in Sydney and then I’d come down to either do a rehearsal or a recording session with the guys in Canberra. I can just remember it’s just such a wonderful feeling to take a piece of music like that and sit down and work through it fairly quickly with a group of guys and then say “ok, here we go, let’s do a take.” So, for me a lot of that Yaraandoo stuff was again very live and vibrant because most of it was the first, second, third take that we put on to the record.

Rob Thomsett: And that was Yaraandoo. We recorded it on a two-track Tascam tape recorder. You know it was just amazing. Over dubbing to hell. Recording in lounge rooms and using lots of local musicians and me playing a lot myself.

Jordie Kilby: With the recording finished Rob pressed up 100 copies and distributed them amongst family, fans, and friends. So, the record was never really a big seller but while having a million selling record is something that many dream of it wasn’t necessarily the motivation for those that were playing on Yaraandoo.

Rob Thomsett: One of the things that really changed my attitude to music was an interview in Downbeat, that i read years ago, with a guy called Elvin Jones who is without a doubt of the greatest drummer that has ever lived. He was playing in a club in New York and there was a whole bunch of drunk people and the interviewer in Downbeat magazine, who interviewed him after the gig, made the point that apparently there was only one person listening to him and the rest were just yelling and talking. Elvin Jones just said, “well, there was one cat listening that’s good enough for me”, and he played his ass off and that really got to me. And about the same time we saw AC/DC at Dickson High School, can you believe that! In fact, we were the oldest there with the two coppers who came and joined us at the back. But it was a great story cause they came out, this was with Bon (Scott) and everyone, there was about 100 kids there. No more than that right. The whole auditorium was empty – it was a bloody gym, but they played their bums off. They played so loud the ceiling was flaking. The painting was peeling off it. A year later they were playing at Wembley in front of 150,000. AC/DC and these guys really understood it. I mean ultimately they’ve got different motives than Elvin but as long as one person is listening it’s worth doing, isn’t it?

You can connect with Rob Thomsett via his website which includes both old and contemporary recordings of his.

If you enjoyed this story and have not yet subscribed to the Sonic Archaeology blog please do so via the link at the top of this page.

Can’t believe acdc played at Dickson college!! That’s wild Cool interview! Didn’t realise the Brian fog well connection – he probably has some cool stories / collection too. Be interested to hear who made up the other bands on their label – they put out a couple of 45s right?? Should have bought your copy when you had it at Woden trash 🙂 let me know when you find a spare hehehe ________________________________

LikeLike